They keep some fun wood carvings at the National Museum of Scotland. It would be easy to spend several days in the bright, well-appointed rooms on Chambers Street, and time seems to vanish in pursuit of Pictish stones or dinosaur bones. I take a sketchbook in during the morning, and when I look up, it’s dark outside.

Of course my eye is always drawn to items and objects from Galloway, and it tickles me to see the decorative door which used to hang at Amisfield Tower, a few miles north of Dumfries. Carved in 1600, it’s a massive and deeply cracked slab which portrays a detailed expression of Samson killing the lion. It’s a dramatic scene, and it makes me smile every time because Samson is not the toga-wearing Biblical character we’re taught to expect at Sunday School. Instead, he’s utterly true to the date of his carving – he’s wearing little breeks and stockings; a natty doublet and a ruff around his neck. Despite his slicked-back hair and a well-combed beard, the main event is his massive moustache which wiggles across his face like an adder.

In his hands, he’s prying open the jaws of a lion which is really no bigger than a Labrador retriever. It has a massive head and funny little paws like hands. The creature clearly knows that the game is up, because its eyes are staring wildly and its tail is straight and burred like a shuttlecock.

In technical terms, it would be true to say that this carving is “not very good” – but it makes its point and it carries exactly the kind of rich, vernacular zaniness which always appeals to me. It’s also fair to say that if the original wood carver had produced a more anatomically correct version of this scene, I would have walked past it without even raising an eyebrow.

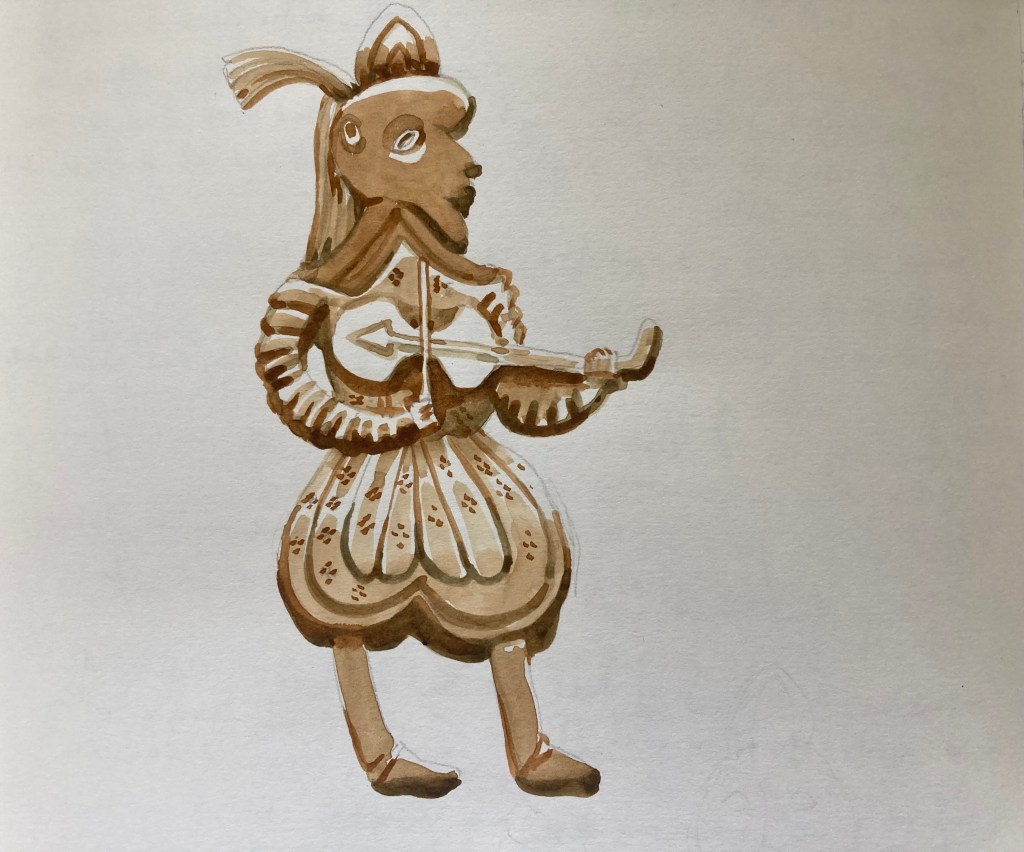

On the other side of the same hall, an oak cabinet is covered in complex and comedic carvings from the late Sixteenth Century. This woodwork used to be part of a bedstead at the famous Threave Castle, a mile outside Castle Douglas. Fine or elaborate carvings were often reused during this period, and it’s reckoned that this panelling later became a wardrobe or a closet – but the real appeal is the craziness of the human figures which prance and cavort across the heavy timbers. They’re playing music and bouncing around like goons – some of their legs bend at improbable angles, and the man on the bagpipes is popping his eyes with enthusiasm.

Like Sampson, this is rough and clumsy work. It obviously lacks finesse, but that’s where the character lies – and I’d much rather hang out with these guys than any number of staid and immaculate designs produced in a high renaissance style. In the same way, I’ve been delighted by similarly flawed work in churches and on stonework which expresses not only the imagination of the maker, but also the technical shortcomings of their ability to make a point.

On an official caption nearby, the po-faced National Museum of Scotland has labelled the Threave carvings as “local work, lively but unsophisticated”. The accompanying sneer is almost palpable, but I would take tremendous pride in the idea that somebody could describe my writing in these terms.

I’m gradually resigning myself to the knowledge that I’ll never learn (or retain) enough information to feel satisfied. Things come and go from my memory, and I have to make my peace with that – but it does irritate me that I’ve been unable to locate two excellent quotes about provincial culture and how it relates to centralised elites. I found them in work by George Eliot and WB Yeats, and each one reflected a shared sense that true originality always comes from outside the mainstream. All “high culture” can ever do is refine and improve itself, like smoothing or polishing a piece of well-worked timber. Cultural gatekeepers manage creativity and steer it through a maze of financial concerns, but they’re unable to synthesise true originality from scratch. Yeats and Eliot are suggesting that provincial imaginations are always looked down upon by the centre – but without these fringes, there is no centre. And those of us who originate in shabby, forgotten corners should feel proud of our ability to see things differently – and to occasionally shock the system by thinking and making things that nobody else can.

Picture: my sketch of woodwork from Threave Castle at the National Museum of Scotland – 11/4/25

Leave a comment