The most famous literary representations of Galloway have been sketched out by authors from elsewhere. As a written landscape, we’re probably most widely known as the setting for John Buchan’s celebrated The Thirty-Nine Steps – drawn from this novel, the catch-quote “I fixed on Galloway as the best place to go” is sometimes regurgitated as a soundbite by local tourism schemes and National Park campaigners, but it contains the germ of a suspicion that you aren’t in Galloway when you’re making that decision. It follows that we’re a place to be looked in at and thought about from a distance; a place where memories are made and taken away again.

Buchan was an avowed Borderer. His focus always lay to the east and the hills around Tweedsmuir, but he returned to Galloway several times in his writing, usually reflecting on time spent fishing in the Galloway Hills when he was a student. There’s no mention of the word Galloway anywhere in his 1901 short story “No-Man’s Land”, but it’s clearly the focus of his attention. He skips around the specific geography and deliberately muddles distances and reference-points, but as he describes the fictional “Scarts of the Muneraw”, he’s very clearly describing the hills above and around the Silver Flowe, either on the bad western faces of the Rhinns of Kells or in the desperate rubble of the Dungeon Hills.

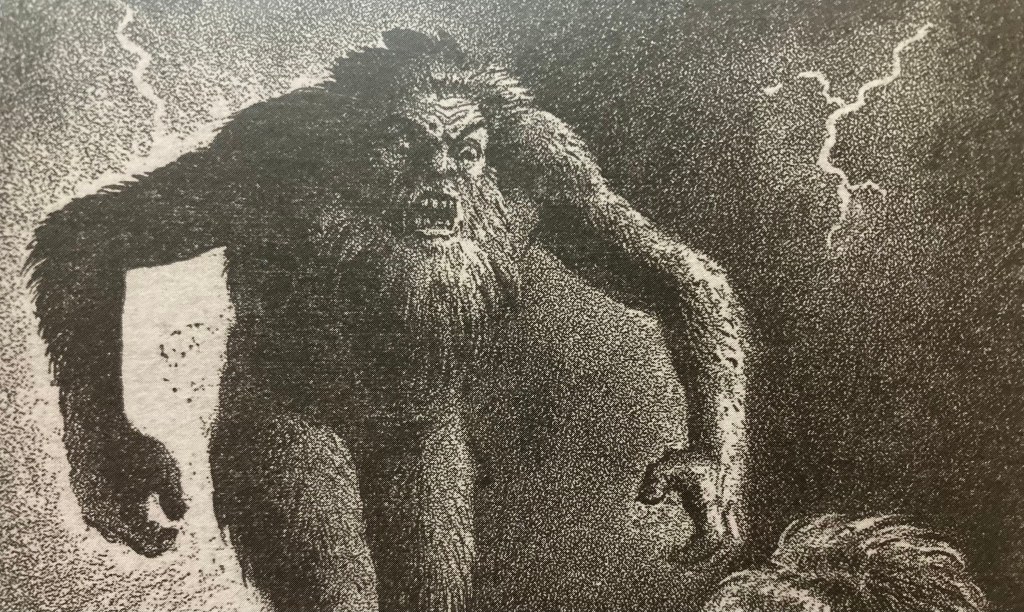

The premise of No Man’s Land is simple – a rising star of Celtic studies at Oxford University is tickled by the idea of a fishing holiday in the hills above Allerfoot, which sounds an awful lot like the high Glenkens. Staying in a shepherd’s bothy, he is immediately intrigued by a local superstition in which sheep are mysteriously stolen and lambs found mutilated with strangely inexplicable wounds. As the plot unfolds, it turns out that these far-flung “Galloway Hills” contain a population of ancient Pictish people, driven underground by thousands of years of persecution. And they’re not just culturally separate… they’re catastrophically bestial; small, sheep-eating cavemen with sharp teeth and nasty minds. Illustrated in 1949 by the artist Alexander Leydenfrost (above), the effect is ramped up still further; these are bloodthirsty ape-men, intent on murder and mayhem. The plot is secondary to some of the descriptive language, particularly in Buchan’s description of a Pictish elder “like a foul grey badger, his red eyes sightless and his hands trembling on a stump of bog-oak”. It’s all great fun, even though the action explodes into a multitude of immediately predictable angles.

It’s no wonder this story has vanished from popular consideration over the last century. If you aren’t from Galloway, it’s just a gently entertaining bit of ghoulishness… but there is something inexplicably hair-raising about the transposition of horror and fantasy to the Galloway Hills. It’s a profoundly moving place, particularly in the last spark of evening when the sun falls abruptly down behind Craignaw and several square miles of ancient boglands fall to sudden darkness. It’s cold and waukrife in the dungeon lanes, and nothing can stand for long without screaming in the screes which tumble down the Wolf Slock. I’ve often felt uneasy out there, but it’s never been easy to explain precisely why.

It took an outsider like Buchan to sketch out these places because there are no native voices here. Descriptions cannot come from inside a void – even the lifelong inhabitant is only passing through. And now I wonder if I’ll ever be able to sleep in the bothy at Backhill of Bush again, or whether I have the nerve to pitch my tent on the slow stoop towards Mullwarcher. I’ll be too busy listening for the knapping of flints, the gulping of blood and the quiet, unintelligible mutter of dark, malevolent Picts.

No-Man’s Land has been reproduced in a few places over the last thirty years. Find it in “British Weird: Selected Short Fiction, 1893-1937”, edited by James Machin and published in 2020. There’s some other good stuff in there too…

Leave a reply to Stephen Shellard Cancel reply