Failing snow, the performance was set for a wet day in December. The singers were arraigned in a line before their parents, but no sooner had they been chased into formation than they changed it. Faced with the almost-touchable temptation of their mothers and fathers, some ran from the ranks to the audience. And it was harder for those who remained in place to stand fast as their lines depleted and gaps opened up where there none had been found in rehearsal. They are already themselves, these kids – and no longer ours alone. The teachers called them by name, and what serves in our absence is changed when we come to see them – their loyalties are sorely strained by such close and confusing expressions of old and new authority.

Teacher had a guitar, and she played it well. But no sooner had the carols begun than the kids fell apart. They sang in twenty seven divergent voices, and the fastest were the first to finish. One found himself done so quickly that he started again from the beginning. Another was still going when the next carol started. Jingle bells was never more discordant and fun, and then they were realigned and pressed into the mould of Away in a Manger, which is harder when you have accompanying actions to remember. Chaos was distilled in a mixture of facial expressions; cheeks blew, frowns folded and emotions played across the choir like bubbles in a pan of porridge. The audience was very present in those kids – a father’s nose and a mother’s grin; we saw ourselves in the winks and gestures of our own parents and grandparents and ancestors we never even knew who skipped the generations and came back to find us as strangers. Then for ten or fifteen seconds, they almost sang as one.

It’s inevitable that my own should have shone most brightly for me, and I wondered if he had been placed in the front row for reasons of reliability. He’s not a bolter, and if the words fail him, he’ll simply smile. He and I have practised giving each other the thumbs up, and I showed him that gesture with a grin. But it derailed him, and he was forced to pause from his chanting to match a reply. He pulled it off in the end, but the work of mirroring my thumb was enormous, and his face was fixed with all the grave enormity of a hen at work on an egg. After my interruption, he couldn’t simply rejoin the group where he found them. He had to sing twice as fast until he’d caught up.

Then Santa came to the front in the guise of a man from the pub. A full belly above bandy legs, he rang his bell and sat beside a fire extinguisher on a squeaky plastic chair. Behind him, a plaque on the wall remembered our Gratitude for the Fallen. Only two people died from the village; one in each war – a light graze, but enough to keep us mindful of the world’s cruel enormity. Teacher asked Santa what the weather had been like at the North Pole and he laughed, saying “It’s bloody hellish, doll”. Then he remembered his script and his audience and explained how the reindeer had almost got lost in the snow. He told the choir that he’d loved their singing, and he reminded them to listen to their Mammies and Daddies and to always be good.

When he first came forward, the kids were anxious of his beard. Just as dogs sometimes hate a man in a hat, they sobbed with fear at a face so strangely obscured. But now they had regrouped, and the more confident ones had begun to circle Santa’s sack like kites above a labouring sheep. They understood that his talking was merely the preamble – but maddeningly, the gift-giving would have to wait until after the tombola and a game of lucky squares. The tension grew. Rain hammered on the windows outside, and one of the stockmen from Barmannoch stopped his tractor to take a noisy telephone call in the carpark outside. One of the Dads behind me whispered that he was a prick, and those who knew him agreed. Santa extemporised, and the tractor quietly filled the hall with diesel fumes.

Amongst the more predictable requests for games and ponies, Santa was asked for gifts which stretched the imagination. I heard one child ask for “a fox bike” and another for “poisonous snake hat” [no determiner]. It was hard to know if these requests represented specific realities or whether they were just an elision of two great but utterly distinct ideas – and the objective was simply to press them together and make something greater still. Santa rolled with these punches, passing the buck and offering to ask the elves. But even the most determined elf would struggle to know whether they should make a bike that looks like a fox – or a fox that in some way captures the essence of a bicycle?

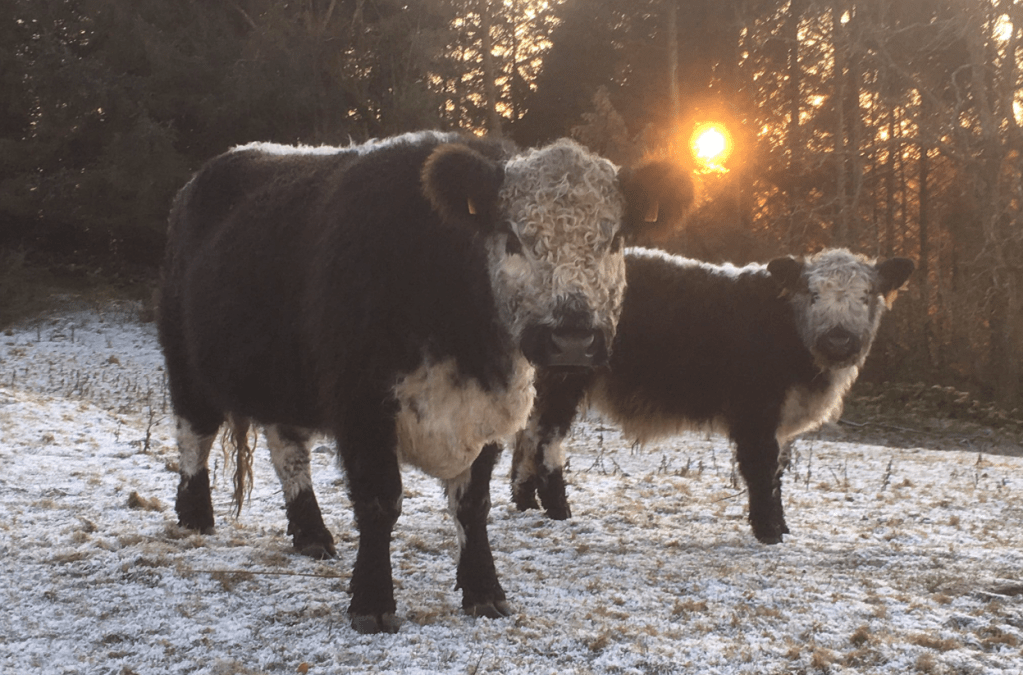

Outside these ripples of silliness, rain ran on through the fingerless trees to the gutters and the runnels of the roadside. It pooled in the playpark and soaked the spruce which had been so carefully decorated by the children in class. Humped against the hedges for shelter, the cattle watched us coming home; cattle which never kneel on Christmas Eve like Thomas Hardy said they would. I know this because I’ve been child enough to check; I’ve carried a lantern to the byre on the stroke of midnight, only to find the beasts standing as they always do in the stalls, and no less wondrous for it.

Leave a reply to Jane Shepherd Cancel reply