For no obvious reason, the idea has come upon me to start painting again, and carrying a sketchbook in my truck has encouraged me to use it often. After a few cursory attempts to draw buildings and plants and people, I became aware that sitting down to draw something requires a level of patience and observation that is quite beyond my normal habit of “look and move on”. I’m also aware that I take photographs all the time, but I almost never return to give them my full attention. And visiting churches and old buildings, it’s not uncommon to be joined by people who come in, take a photograph and leave again in less than a minute. I often do it myself, and it’s made me wonder what we’re missing.

At Colva church near Glascwm last month, I pulled out my sketchbook and sat for almost three hours drawing the building and the surrounding hills. Not everybody has such time to squander, but I only stopped when it was too dark to work and even the robins had given up calling for the dusk. And now when I look at the sketches I did that evening, I’m reminded of the place in new and interesting ways.

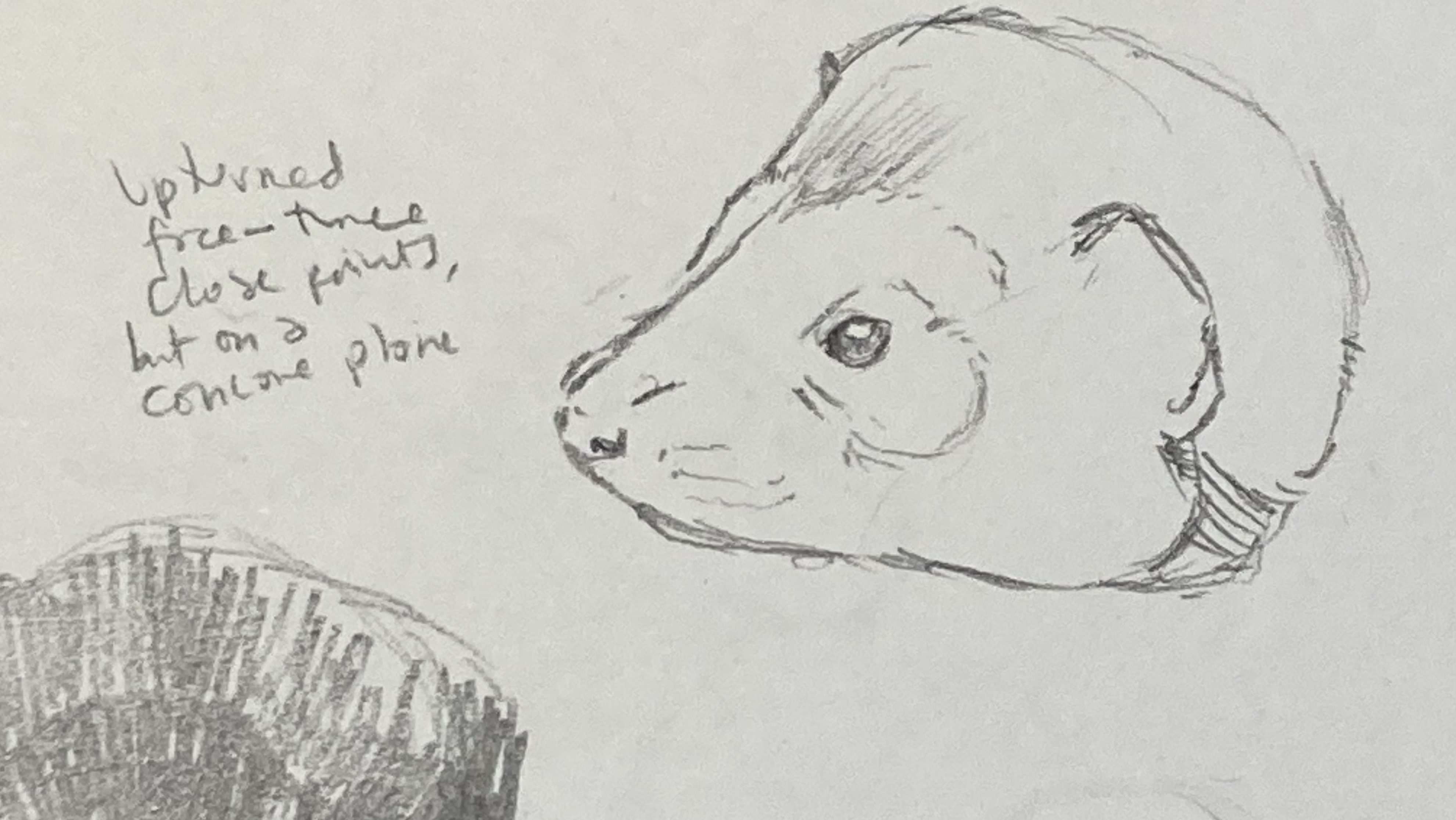

Focussed upon these thoughts, my eye was drawn to a mink which turned up in a cage trap on the riverside below the house. Everybody knows what a mink looks like, much as a quick search online will reveal a host of high resolution images of Colva church. But I was keen to try a few sketches on a warm afternoon in the sunshine, wondering if the exercise would teach me something new.

The results were mixed, and many were too poor to be shared here. But in ten or fifteen separate attempts, I found that I was able to capture a handful of accuracies – a line in the right place here, or one correct shape in a mess of errors. Next to these small victories, some mistakes were oddly closer to the truth than I realised – much as a caricature exceeds the mark but draws attention to the fact. I’m now even tempted to combine these sketches together for a proper painting, and the joy of doing that would be to completely short-circuit digital imagery, photographs or “reference” resources which have often turned my paintings into the process of copying reality. It would be something that I had seen and made permanent with only my eye, my brain and my hands to help me.

Whatever transpires in artistic terms, the project was revealing because it served to highlight the fact that for all I have come across mink a thousand times, I’ve never really seen one before. I was surprised by that, and it’s worth recording what I took from the experience.

- The eyes and nose of a mink are extremely close together – three equidistant points which all lie at the front of the skull. That leaves an awful lot of the head unaccounted for, and the shape itself is almost impossible to sketch with any regularity. Not only were the powerful sagittal muscles able to change shape at will, but the contours of the fur moved with it.

- The eyes look small and black, but they’re not. They’re brown, and their shape is always shifting. They can bulge with excitement, then sink to become watery slits in the course of a single thought process.

- The ears are maddeningly elusive; get them right and you’re halfway there – but even the smallest error will spell disaster. At first glance, those little crescents look like a simple ripple of fur – but they’re continuously moving, even when the mink itself is asleep.

- Unlike a ferret or a stoat, a mink’s nose kicks very slightly up towards the snout. This was hard to fathom at first, and most of my initial sketches were made on the assumption that I was simply drawing a black pine marten. In reality, the physiognomy is entirely different – and reflecting upon this observation later in the day, I reckoned that the upturn allows the nostrils to remain above water while the nose itself is submerged. Otters are the same, and it’s an echo of the hippopotamus or the ludicrously excessive Indian gharial – and it’s perfect for an amphibious ambush.

- Mink have no philtrum – their top lip runs in an uninterrupted band from one cheek to the other. And that’s irritating, because drawing a line downwards from the nose to the middle of the mouth is an easy way to evoke a shape when you’re sketching. But there must be some kind of hydrodynamic benefit to a leading edge which is completely smooth, because now I realise that otters are the same.

- The white flash of a mink’s chin is almost always hidden. I went to great lengths to draw my mink with a white chin and couldn’t understand where I was going wrong. It took me an embarrassingly long time to realise that while mink undoubtedly have white chins, they’re only show either by accident or in a momentary flare of aggression. Nine times out of ten, that chin is tucked neatly away under the muzzle like a mattress under a duvet. And I had wasted a lot of paper trying to make that animal look the way I thought it should.

- I had never given a second’s thought to the shape of a mink’s feet. They’re madly complex; high arched and well-jointed right down to the claws. The toes are webbed, but the webs themselves are subtle and pink. I was grabbed and scratched by a mink once. Looking at those feet, I can understand how they caused such harm.

After the initial shock and bother of my disturbance, my mink went to sleep in the sun at my feet. In order to draw it from a range of angles, I had to actually wake it up and provoke the curiosity I was expecting. At times it was so entirely asleep that it began to twitch as if dreaming. This semblance of placid domesticity was not to be trusted – if I had put my fingers inside the trap, I would have lost them.

I have killed many hundreds of mink over the years, but trying to draw one overturned many of my shorthand assumptions of what these animals really are. This one died soon afterwards, but I am ever-more distrustful of expressions like vermin or pest. Mink are fascinating and beautiful animals, and there is always value in looking harder and for longer at even the most everyday things – given that this has become my creative mission-statement, it makes sense to sketch alongside writing.

Leave a reply to Patricia Digby Cancel reply