There are several biographies of Henry Williamson, and each one sheds different light on the man himself. The best and most useful books are probably Tarka and the last Romantic by Anne Williamson and Henry Williamson – a portrait by Daniel Farson. Both were published after Williamson’s death, and they offer a similarly defensive perspective on the writer’s legacy.

Anne Williamson engages with her father-in-law’s fascism and politics, but she is constantly at pains to exonerate him on the grounds of his political naivete. She argues that he was simply too passionate to be held fully accountable for his views; that he belonged to a different and more idealistic era of wonder and purity and truth, and that he could not grasp the cynical enormity of Hitler’s ideologies.

It’s useful to realise that accusations of Henry’s wickedness have faded nowadays. Perhaps we remember that he was a fascist, but we don’t know very much more than this. In this context, a full-blooded defence of Williamson which runs across dozens of pages comes across as alarming – most modern readers didn’t know he was that bad, so exhaustive attempts to defend him raise all kinds of suspicion.

Daniel Farson takes a similar line on Williamson’s politics, suggesting that he was out of his depth… but he does at least concede that Williamson was downright inflammatory and provocative when he felt cornered. It was one thing to hold outrageous views and quite another to deliberately irritate the people around him with silly gestures. For example, there was no need for him to paint his car with the lightning strike symbol of Oswald Mosely’s British Union of Fascists, just as it was daft to overstate the extent to which the British state had suppressed him during the War. The best evidence suggests that he was simply invited in for a chat in the local police station, but Williamson seemed to wear this threat as a badge of honour, overstating or exaggerating it out of all proportion to heighten a mood of persecuted genius.

Williamson seems to have been stuck in a cycle of fury and escalation which was exacerbated by his own self-inflaming energies. He was stubborn, defiant and utterly unapologetic. Farson and Anne Williamson reread these characteristics as “forthright, courageous and devoted” – but their obvious underbelly always goes unexplored.

Later in his book, Daniel Farson enters into a complex exploration of Williamson’s view of himself as a writer in relation to his peers. It seems clear that Williamson felt underrated and unloved – he believed that he deserved more praise from the world, and it galled him to see others rise beyond him. But in pursuing these threads into a community of case studies and anecdotes, Farson spins out a web of gossip about writers writing across one another in a bid to steal glory for themselves or for other writers. It’s grim and dull and nobody cares why various feuds played out across a self-important class of ageing, pretentious creatives.

As I work on into reading Williamson’s back catalogue, it feels ever more obvious that the bulk of his best writing was published before the Second World War. He wrote copiously after that point, but none of it shone in the same way – and much of it is laced with a feeling of contrivance and desperation, as if the work itself was secondary and the increasingly reedy point was that everybody should listen to Henry Williamson – and recognise his greatness. A subtitle to Farson’s book is: “The heartbreaking story of the author of Tarka the Otter” – which invites us to look upon Williamson’s numerous nastinesses and say only “how sad”. Aside from his shocking experiences in the First World War, Williamson’s life was very much in his own hands – it takes an awful lot of imaginative legwork to describe it as heartbreaking.

There is one Williamson story which stands out from the biographies I’ve so far read. It’s only present in Daniel Farson’s book, but it leaves an ugly taste in the mouth because it describes the author killing a kitten by dashing its brains out on the floor of his Norfolk kitchen. The creature had evidently eaten a piece of fish which was being saved for a special guest, and Williamson’s reaction to the loss was one of irreconcilable fury.

This is an unsubstantiated anecdote – so if it wasn’t true, it could easily have been left out of the biography altogether. But it matters that Farson felt the need not only to include it but also to defend Williamson. He suggests that it was during a time of rationing and that fish was hard to come by – that Williamson’s natural passions were never far from the surface, which explains how he came to be such a wonderful artist in the first place.

In the context of Williamson’s thinking, it’s not hard to believe that the incident is true. It wouldn’t have been a big deal for Henry and while I have often done the emotional legwork required to be “be ok” with death as presented in his books, this is an oddly cold-blooded and reactionary expression of fury against an innocent animal. For all that Williamson claimed to weep tears over the death of hunted animals, this is just pointless destruction in the name of uncontrolled passion.

It’s a weird paragraph because in his attempts to exonerate the author, Farson reveals the lengths to which he is prepared to go in order to present a positive view of the man. He’d have us believe that smashing a kitten to bits is the rational act of a complex but ultimately loveable man. In that moment we have to wonder what else is being spun in Williamson’s favour – and what would it take for Farson to concede that he could sometimes be a bastard?

Daniel Farson was a friend of Williamson, just as Anne was his daughter-in-law. Williamson has been memorialised by people who loved him and who absolutely refused to see the worst in him. They liked to believe that he was complex and wracked with contortions of genius against which nastiness could be offset – perhaps that’s the hook for these books which seem to challenge prevailing narratives that Williamson was a horrible man.

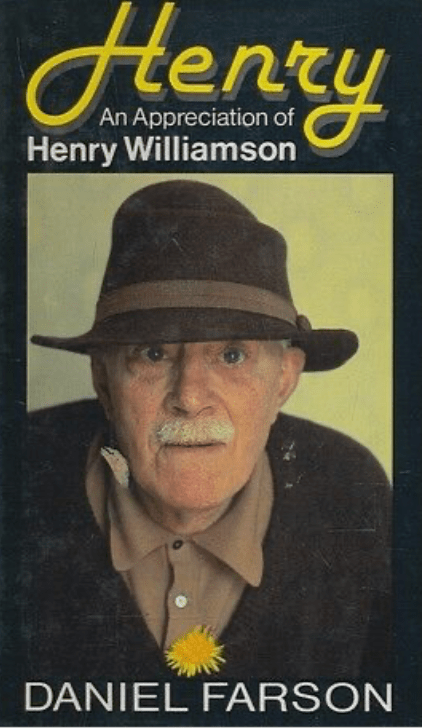

Farson wrote another book about Williamson which has a picture of the author on the front cover. Williamson could be very vain and hated Farson taking his picture – but this image is by far the worst I have ever seen; the obviously wizened Williamson is cross-eyed and frail, gaping out from beneath a big floppy hat like a lost puppy. He has a dandelion in his buttonhole – a gesture to Richard Jefferies, but this Williamson is so wrecked and dishevelled that it looks like the flower was jammed there as a joke by teasing children. Placing this picture on the front cover of “Henry: an appreciation of Henry Williamson” is very much out of line with the hale and hearty author in his prime – but is it another attempt to recast him as a gentle, lovable and only slightly batty old chap?

These books demonstrate a need to recast and remould Williamson’s legacy, but their arguments often seem to ring too loudly – and while there’s always more evidence to consider when it comes to deciding how we feel about people and ideas, there comes a point at which we really are able to draw some broad conclusions. In Williamson’s case, it’s difficult to see how the good could ever outweigh the bad – but it’s also hard to know how far our opinions of the man should colour our opinions of his work.

Leave a comment