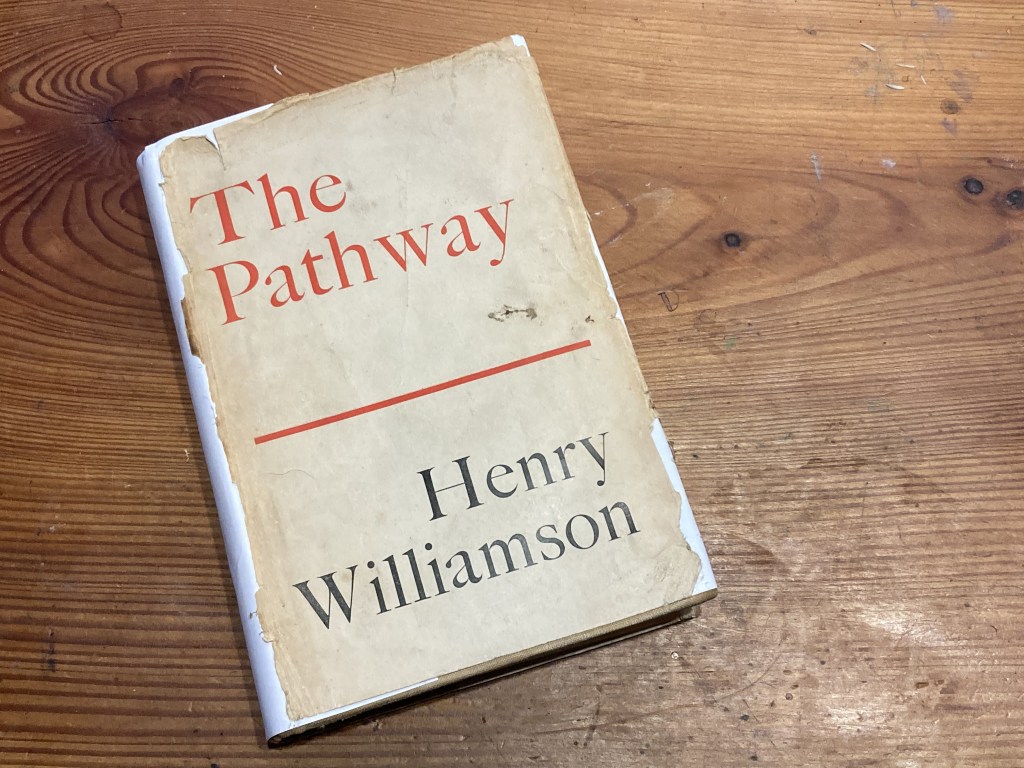

The fourth and final instalment of Henry Williamson’s The Flax of Dreams series is simply called The Pathway. The name has an evangelical ring to it; it echoes Christ’s exhortation that “He is the way”, and it’s fair to say that mystical zeal rings throughout this book. I’ve sometimes been flippant in my criticism of Henry Williamson, first out of ignorance and latterly through a sense of shock that one man could express a such an extraordinary level of self-belief. But now I have to concede that The Pathway does make an extraordinary impact – The Flax of Dreams is an outstanding literary achievement. Perhaps they’re not the kind of novels you’d read for fun, but as an exploration of spiritual development, they’re deeply fascinating things.

The book begins on the Devon coast where a mish-mash of people from the Ogilvie and Chychester families are living together in a rambling old house. They’re the broken-hearted survivors of War; women, illegitimate children and old men living a simple rustic existence in the dregs of Victorian grandeur. Amongst them are Mary Ogilvie, the woman who has clearly been romantically devoted to Willie Maddison since the first book in the series. She’s had to endure his fads and his fancies for almost twenty years, picking up the pieces of his reckless love for other women and his relentless self-pity.

When Willie Maddison stalks onto the scene, he’s undergone dramatic changes from his days in Folkestone and The Dream of Fair Women. He’s been on a pilgrimage to France and Germany, and he’s returned with his eyes opened to mankind’s enormous tragedy. He’s been purged by the experience – he’s no longer quite human, moving instead across additional dimensions of spiritual acuity. He sees it all now, and if he sometimes came across as weedily presumptuous or fey in the previous novels, that same confidence has now been transmuted to a deep and gentle calm. All his former frantic urgency to be recognised for his greatness has passed. He has become Christ.

Mary’s cut from the same cloth as Willie. They’re both ascetic idealists with their eyes brightly focussed on nature and earthy simplicity. The Pathway follows the development of a deep and spiritually balanced relationship between the two. At one point, they’re engaged to be married – but their love can never blossom. In a final act of mystery and magic, Willie is drowned in the nearby estuary. This moment of fatal fulfilment is carefully trailed all the way through The Pathway – it has to happen, and there’s a neat circularity in “the natural soul”’s reversion to nature.

It’s tempting to read these novels as autobiography – and to read Willie’s failings as Williamson’s. But if you really work to pull Willie and Henry apart and treat the writer and the character separately, this book does gather real punch and momentum. When Willie’s holding forth at length about the weight of his own genius or the spiritual burden of being Christ, it’s tempting to look over his shoulder and say “oh my god Williamson you arrogant bugger, surely this can’t be how you see yourself?” – but if you treat Willie as an exaggerated expression of Williamson’s self-belief, he becomes a character with own urgent agency. Freed from the writer’s hand, he can be confident in himself; he can be egregious or confrontational or self-pitying because he’s not an actual man – he’s just an idea. Williamson clearly loves Willie, but we don’t have to love him too. He’s interesting, even if he never becomes likeable.

I have wondered whether to recommend The Pathway as a standalone book. I wouldn’t recommend The Dream of Fair Women to my worst enemy, but every book in this sequence performs a different role. They add up to make clearest sense in The Pathway, and this book does work in isolation – it probably serves as a useful companion to Tarka, explaining Williamson’s wider philosophy and the germ of his future politics and controversy. There’s also a neat overlap in the way the two books deal with otter hunting, which was the start point of this project for me.

Willie Maddison doesn’t like the sport, but he understands how it fits as part of a world order characterised by atrophy and a lack of original thought. Willie’s experiences in the War reveal not only the universal commonalities of man, but they also shed light on dusty and decrepit institutions which are perpetuated for the sake of habit and hide-bound insensitivity. Otter hunting forms part of a low-brow, unfeeling world in which pagan brutalities of childhood are ossified into tradition. It’s a point of stagnation; a spiritual stunting – but no individuals are to blame. The whole system is broken, and it’s Willie’s role to break ground for change.

Moving like a new Messiah through the spirits of local boys, Willie accepts their adolescent savageries as part of a natural order which should be kept free from the perversions of discipline and education. Willie seems to endorse lying, laziness and cruelty in young boys – not only because he was vilified for expressing these same flaws, but because he believes they’re the natural expression of a wild human nature. Importantly, Willie is certain that boys will grow out of these behaviours into brighter levels of enlightenment – but importantly, they do it themselves in their own time and in their own natural ways. In this context, otter hunting fits on a continuum of natural ethics in which everything can be explained or understood as part of a progress towards clarity and revelation.

Willie is the fullest expression of the realised, natural man. Those who resist his visionary influence are simply bound too deeply into the old way – but they will change too – because a failure to engage with the deeper, mystical self (sparks of which are called Khristos) is a commitment to perpetuate the perversities of the past – inequality, conflict and greed. As it stands, the existing system is destined to cycle through an escalation of ever-more tragic wars. To break the cycle, we have to break the system and restore faith in the innate natural spirit.

Willie has to die in the end, but the scope and emotional impact of this book far exceeds many of the low-points in the series, not least for its expression of old country – Devon in its roseate heyday, and countryside writing of the highest and most spotless order. Even if none of Williamson’s pseudo-theological philosophising rings your bell, these books shine for their descriptions of birds and wildlife on the hills and sand dunes which lie around Georgeham, Bideford, Braunton and Appledore. Some of the local folk are lightweight caricatures, but their work catching salmon, planting trees and trapping rabbits has a palpable heft and value in the context of ancient human tradition.

Searching for Williamson last year, I visited this coast and was profoundly impressed by it – even in its current guise as a gaudy tourist trap. The Flax of Dreams can be read as a banner of love and enthusiasm for a place and a time, and it’s an extraordinarily ambitious and creative accomplishment. I’ve read many books which I’ve enjoyed more or taken more pleasure from, but you don’t exactly read Williamson for the banter. In The Flax of Dreams, he’s serious and focussed in the full stretch of his most unsmiling self – and there’s a tremendous amount of emotional colour to fuel the experiment of thinking. But while setting out to read all of Williamson’s work has so far been a varied experiment, I do think that Willie Maddison’s story matters – even if it’s only as a deeply-felt expression of passion and love for the world.

Leave a comment