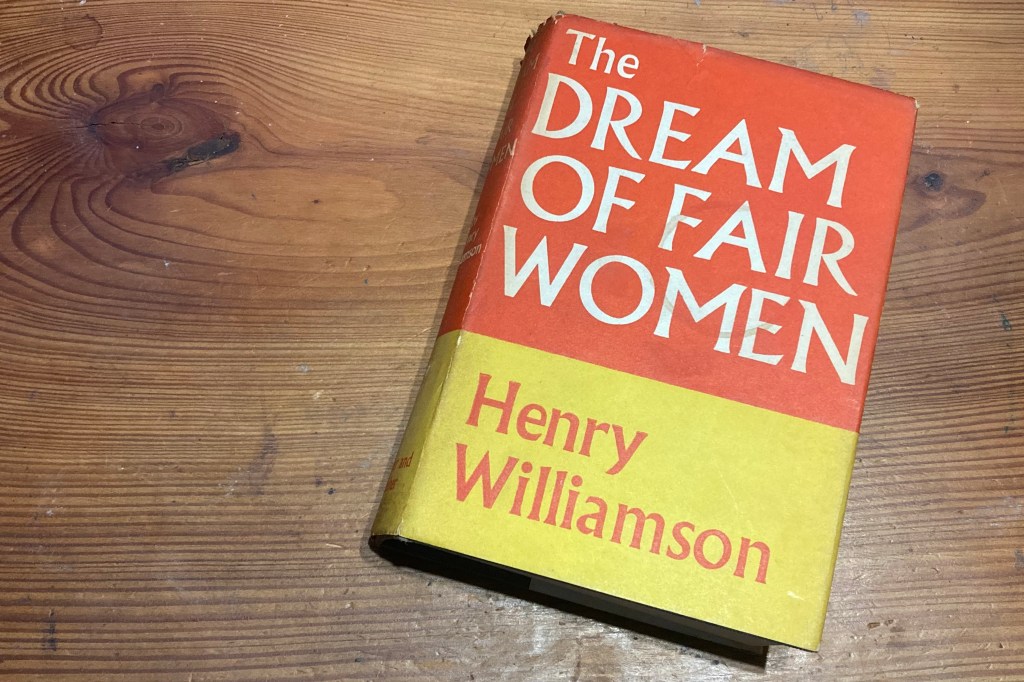

The Dream of Fair Women is the third book in Henry Williamson’s The Flax of Dream series, and it strained my interest in this writer to the very edge of breaking point.

The Beautiful Years was brightly winsome and Dandelion Days offered moments of excited nostalgia – but both were rooted in presentations of nature and rural landscapes. Even at their ugliest, they were still quite fun. The Dream of Fair Women leaps into different world altogether; most of the action takes place in a well-appointed townhouse in Folkestone where the “Bright Young Things” aesthetic of Evelyn Waugh or Noel Coward crashes into the perpetually downcast grimace of Willie Maddison. Henry Williamson is many things, but he is not a light or funny writer – as Willie moons and sulks his way through a collage of chattering parties, tennis tournaments and romantic whisperings, this book drags like a glacier.

The story begins a few months after the First World War in the beautiful scenery of coastal Devon. Although it’s heavily trailed and anticipated in the previous two books, there’s no military action in The Dream of Fair Women. We view glimpses of the Somme and Gallipoli through Willie’s memory, but the experience is abstract and illusory. The human cost is almost completely skimmed over – the narrative baldly explains that almost every schoolboy character from The Beautiful Years and Dandelion Days has been killed during the course of the War. None of these deaths are explored or discussed – not even the death of Jack Temperley, who has been a major supporting character until this point. Their fates are simply listed in a single and somewhat perfunctory paragraph in a chapter which is largely devoted to other ideas.

It turns out that Jack’s death is actually more noticeable before it happens than after the event. I wondered why Williamson trailed the fact that Jack would die as a plot-spoiler in Dandelion Days. Now that I’ve read The Dream of Fair Women, the effect is even more confusing because Jack’s death has no impact on what happens next. Aftershocks of War run throughout this book – the narrative voice calls Willie “Maddison” now, complete with the rank of Captain and a breast full of famous medals. The boy has changed, and the transition is an entirely emotional one. Perhaps the list of Maddison’s dead friends is too fresh and raw to be discussed openly – but the lack of closure feels bizarrely open-ended from the outset.

As the novel begins, Maddison has “gone native” in an abandoned cottage on the seashore, surrounding himself with a menagerie of wild animals including (perhaps importantly) an injured otter cub called Izaak. Isolated and deeply injured by his war-time experiences, he’s flung himself into a swirl of rustic escapism. He takes long walks and spends his evenings drafting an idealistic tract on human connectedness and the immediacies of the natural world – it’s an ambitious attempt to fuse all of human goodness into a single edifice of beauty and light. Maddison has called it “a Policy of Reconstruction”, and he works across the book at mad hours to the tune of owls which appear at his window and swallows which roost under the eaves above his bed (a camp-bed strewn with bracken).

Maddison’s fantasy world is shattered by the arrival of Evelyn Fairfax and the love affair which develops between them. Chasing her home to Folkestone, he neglects his menagerie and the animals desert him; he gives his spaniels away (and when they find their way back to him, he gives them away again) – he’s finally found the love he always wanted, but it comes at the cost of his native innocence.

But even as Maddison throws himself into this experience of love, it’s never entirely clear why Evelyn is the one for him. At times it seems like she exists only to reflect his emergent greatness – to challenge him (within reason) and to encourage him to ever-greater expressions of creative wonder. But she’s wildly temperamental, and it gradually emerges that she is already married and has a daughter with one Major Lionel Fairfax. That’s not all – she’s running a system of confusing and strangely passive affairs with men across the South of England. Willie’s sombre and unnervingly intense brand of romance is being squandered on a woman who cannot return his love.

Against every impulse to throw this book away, I fought my way through a two-hundred page section at the heart of this book which follows Willie’s romantic pursuit of Evelyn. It was like swimming in mud, and while I devoted a considerable amount effort towards trying to work out how Evelyn’s system of affairs and infidelities worked, the effort simply wasn’t being repaid. These scenes present a chaotic expression of social life in the aftermath of the First World War; pen portraits of busy introspection amongst a gang of people who seem to think only of themselves. It’s been a year since the War ended – it’s too late for these people to fight and too soon to recover anything like a sense of lightheartedness. At their best, these sketches reveal the social and cultural atmosphere of an entire generation completely bowled over by the experience of War and wondering what on earth to do with the rest of their lives. At their worst, acres of dialogue between Willie and Eve are squandered on exchanges which feel like:

“Darling, why all this thusness?”

“Oh Darling, do tell me that you love me”

“But Darling you know I mustn’t”

“Oh Darling you are so cruel to me”

“But Darling don’t be beastly, you know that my heart belongs only to you… but…”

“But what Darling?”

*sigh*

“Nothing Darling… only that if all the world were different, Darling…”

Maddison’s relationships are always tortured by the magnitude of his own personal journey. His women are devices through which his majestic self-awareness can grow and magnify itself, but he is sometimes skewered when they turn the spotlight back upon him, offering acute observations of his own flaws. Maddison is wounded by these criticisms, but accepts them because he feels so deeply – they become more emotional fuel for the fire – but when Evelyn teases him for his extraordinary sense of self-importance, he refuses to laugh or defend himself. Instead, he goes limp and enters even deeper shades of heartache and self-pity.

Willie Maddison genuinely believes that he is an enormously significant figure in the world – he even describes himself as a prophet or a new Messiah. But when those comments are played back to him, he doesn’t retract them in embarrassment – he actually endorses them. His only note or amendment is that his destiny is desperately more complicated than they’re making it seem – he’s vast, and they’re just not getting it yet. To modern eyes, Maddison is outrageously arrogant, and if this is a true rendition of Williamson himself, there are some major implications for how we view his work nowadays.

Evelyn is dreadful; there’s nothing endearing about her at all. It’s important that Maddison should feel crushed by Evelyn’s awfulness – but I wish that readers didn’t have to be crushed by it too. There were many times when I worried that Williamson had deserted me altogether, but it turns out that I was probably supposed to hate the things I hated about this book. Maddison is being deliberately tossed around in a whirlwind of loudness, superficiality and unreason so that he can ultimately climb out of it and rebuild himself. He has to understand that people are not always what they seem – his Dream of Fair Women is exactly that – it’s a dream which expunges any remaining vestige of emotional innocence. At the end of it, I felt just as Willie does – worn out, weeping with disgust and desperate to go where the birds are singing.

As much as I struggled with this book, the effort was repaid by several fascinating glimpses of Williamson’s own emergent philosophy; his feeling that post-War society had fallen out of touch with the world’s bright glory; that even in its terror and hardship, the War had thrown up moments of clarity and truth which transcend religion, politics and nationality. Through this story, Williamson seems to express a belief that it’s time to move forward; that the future belongs to a new species of youth and immediacy which has been enlivened by the horror of war. He seems to say that civilisation has lost sight of “ancient sunlight” – and that it is down to a handful of celestial and luminous personalities to restore a vital, universal order of connectedness.

Leave a comment