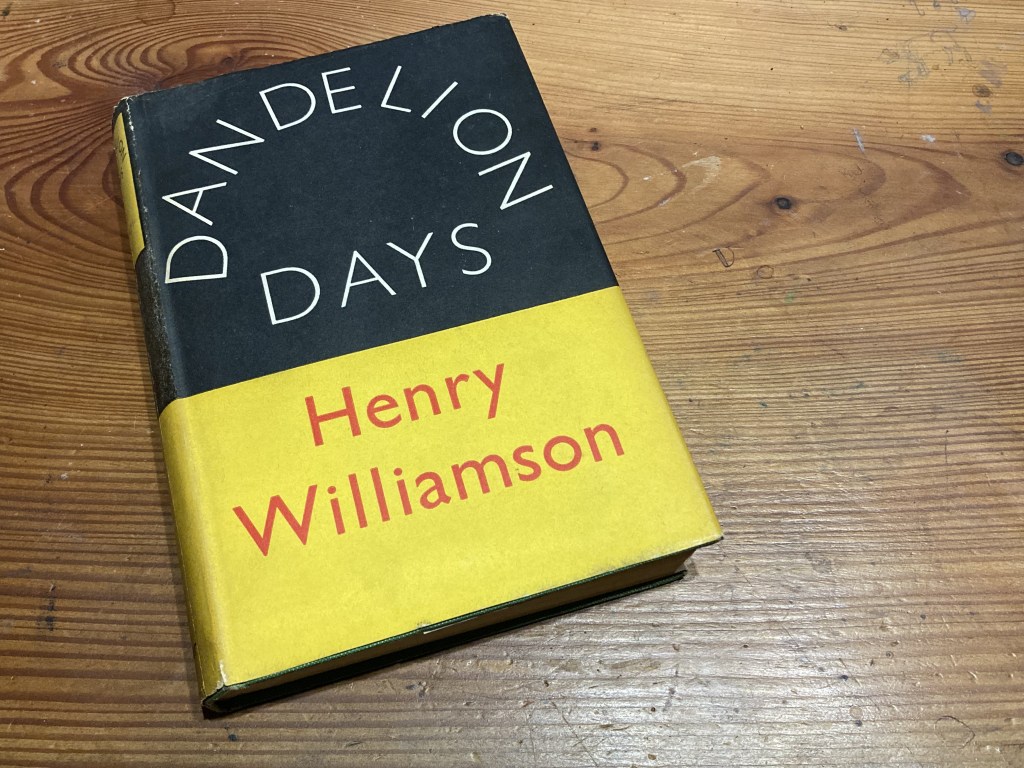

As The Beautiful Years drew to a close, we left the nine-year-old Willie Maddison locked into a fantasy of wildlife and friendship with the local farmer’s lad Jack Temperley. Dandelion Days picks up the thread after an interval of six years, but an author’s note explains that while these books were written in sequence during the early 1920s, the second book was almost completely rewritten in 1930. That’s interesting, but the same note later includes an open admission that both Willie and Jack end up dead; Jack in Flanders and Willie by some unknown cause. It’s a monumental “plot spoiler” to throw up before we’ve even reached page one, and I was surprised by it.

On their initial run, the first The Flax of Dreams novels sold very quietly indeed. Williamson’s real fame came in 1927 with the publication of Tarka the Otter. Critics understand that Tarka was written in the foreknowledge that it would be popular – but it wasn’t the kind of work Williamson wanted to produce. He wrote the otter book as a way to grow his profile so that books like Dandelion Days would reach a wider audience. The plan worked, and given the sudden success of Tarka, it’s not surprising that Williamson would want to refresh his back catalogue in the face of heightened demand – but it doesn’t explain why he should give away the story in such blatant, unrewarding terms.

As if the initial spoiler wasn’t enough, Dandelion Days concludes with a series of epigraphs about Jack’s death (which hasn’t happened yet) and trails Willie’s involvement in the First World War (which hasn’t been declared). There’s a similarly ominous clang in the last sentence of the book when it transpires that Willie has left school with the whole world at his feet… and it’s July 1914. Any investment we’ve made in the characters by this point suddenly feels taut with expectation… not because War will bring jeopardy, but because Williamson has explicitly told us that Jack and Willie are about to die. It’s baffling.

The Flax of Dreams is utterly dependent upon the First World War. While the first two books in this series look like a wonderful spiritual engagement with nature and childhood, they’re actually devoted to fleshing out of a character who is complex and sensitive enough to do the War justice. Williamson’s objective is pretty transparent, but Willie is his blind spot because this is autobiography disguised as fiction. Williamson loves willie very dearly, but the boy is clearly a rendition of the man himself – (the author was often called “Mad Williamson” at school, so it seems obvious that his pseudo-fictional hero should be called “Willie Maddison” – aka “Mad Willie”). The plot has been tweaked and adapted, but the essence of this protagonist is utterly true to life.

Here’s where things get confusing, because while Willie is a vehicle for exploring and explaining Williamson’s own creative drive, the boy is actually a pretty unappealing character.

Willie’s often selfish and withdrawn; at times, he’s performatively contradictory and unhelpful. Williamson presents the boy as a natural genius who is at one with the sun in a pagan ecstasy of experience. He’s everything that Williamson believed himself to be – but modern readers could be forgiven for thinking that he’s a self-obsessed little brute. Gliding between a profound engagement with natural history and a deft awareness of superstition and native magic, Willie performs improbable feats of raw, intuitive engagement with the world – he slips across social boundaries, admired by hum-drum paupers and housemaids but always retaining the social propriety of a little gentlemen. He’s academically capable, but he chooses to squander these talents through a pattern of disobedience and rebelliousness. His romantic love is explosively melodramatic and his male friendships are profound and almost sexual in their intimacy, (some of his engagements with other boys are actually, actively sexual) – but he is always the trembling, tremulous hart with the flickering eyelashes, swayed by the movement of wind in the trees and flighty as a moorland bird. Most irritating of all, by trusting to his instincts and emotions, Willie is always right – if not in the detail of the moment, but right according to a wider universal plan that is invisible to everyone but himself.

It’s actually quite acceptable to skip longer passages of Willie’s natural rapture. Much of this stuff is borrowed from the writing of Richard Jefferies, who Williamson worshipped. Jefferies was often good on pragmatic descriptions of rural life, but he had an unusual tendency to think in terms of mysticism which has fallen deeply out of fashion nowadays. Jefferies was the original stamp of what Kathleen Jamie later termed “the lone, enraptured male” – she was talking about Robert MacFarlane, but he’s just the latest expression of a slowly unfolding cliché which reaches back to books like Jefferies’ almost unreadable autobiography The Story of My Heart (1883). Williamson adored this book, and the name Dandelion Days is directly taken from Jefferies’ work – to a point at which there are moments when influence blurs towards direct plagiarism; young Willie lies barefoot in meditation on the florid hill, conjuring profound aphorisms on the undersides of nodding scabious flowers while the smiling sun bends his immortal, immemorial light upon the dustiness of an ancient land etc etc.

Williamson sometimes seems to recognise that Willie is not a very lovable character. There are moments when the boy is deliberately candied up with gestures of sweetness and acts of gentility – but these feel hollow and inconsistent because Williamson doesn’t really believe that Willie needs to be likeable at all. Chances are that Williamson wasn’t a very likeable child himself… and therefore “being likeable” is not the point. Whatever Willie is becoming, it’s too profound and significant to be influenced by trivial notions of popularity. The effort required to make Willie likeable seems to stick in Williamson’s throat, but the author knows that readers will baulk at the unsugared pill of the boy’s egregious “genius”. Readers need to want to share Willie’s journey, so Williamson is forced to invest the boy with a degree of charm – and it follows that when Willie is charming, the charm is oddly artificial. We know that if it were up to Williamson, the world would bend to the enormity of the boy’s emotional vastness and forgive him anything anyway.

Dandelion Days really is charming at times. Modern readers are extremely suspicious of nostalgia and whimsy – these are guilty pleasures in a world of cynical progress and competitive edginess, but the sweetness of Dandelion Days does work in its way. It’s a beautifully colourful book, full of prettiness and wonder – and these things do have an impact, even if we afterwards deny it in public. But with an excessive (borderline tedious) emphasis on school teachers with silly nicknames and hi-jinks between classes, this does feel like a book written by a precocious young man – a man who was very recently a boy.

The first version of The Flax of Dreams was written and published when Williamson was in his mid-twenties. He’d been through a terrible War, but he hadn’t done much else with his life. At the time of writing Dandelion Days, Williamson’s contemporaries remember that he preferred the company of children to grownups. As part of a project at my own school, I was encouraged to speak to veterans from the Second World War about their experiences. Even then, I was struck by their sense that in fighting a war, they felt like they had missed part of their own lives – they had been asked to give up the freedom of their youth. Williamson’s books lean so heavily upon school content because they’re building a character and a fine sense of innocence which can later be crushed to dramatic effect… but at times they also feel a little childish because the War has left Williamson feeling and acting like a bit of a child himself.

Dandelion Days was harder to read than The Beautiful Years. It’s not easy to spend time with Willie, but it is useful to follow strands of Williamson’s worldview as it develops and evolves towards his later writing. There are some beautiful passages and the pages seem to turn themselves, but it’s worrying to find Williamson’s exceptionalism often grows by the chapter. Through Willie, he reveals a staggering confidence in his own genius… which ultimately leans towards some shocking expressions of arrogance. In that light, this book adopts a disturbing subtitle – something like “Dandelion Days: why my natural soul is deeper and more penetrative than anybody else’s”.

Leave a comment