There was a rustle in the fallen ginkgo leaves, and a glimpse of movement through darkened railings. I looked for more detail and found myself almost nose-to-nose with a fox. In a glow of the streetlights, he sat up like a traffic cone and showed me his breast, stretching slightly and sending a ripple of prosperity down the length of his back. Beyond him, a light, metronomic “tick-tick-tick” suggested that something else was trotting through this South London playpark. Sure enough, a second figure materialised from the darkness. It came to sit beside the first, and the only way you’d ever hope to see a fox in such detail in Galloway is from the study of a corpse. Otherwise, my wider engagement with these animals is always tiny against an enormity of context. When I write to describe foxes here, nine tenths of my time is devoted to the light and the texture of grass or birchwoods where foxes have passed by. The creatures are only glimpsed; sipped and engaged with like ghouls. And when they’re dead, it’s steam from their wounds and the drips of blood which foregather on the points of their noses that catch my attention. They’re never a subject in their own right – like snow, a fox is only the colour of the light that’s cast upon him.

Out in Southwark, the fox is front-and-centre – he’s an almost lurid “page three” of overexposure, leaving nothing to the imagination. But I couldn’t resist the chance to squeak to these predators, just as I would squeak to draw them in range of my rifle in the real world. There’s a laughed, apocryphal story that foxes in cities respond better to the rustle of takeaway wrappers than they do to the wail of a hare. It’s true that my call did nothing to draw them in, but they do know what rats are – and they were excited by the squeaking sound I made between my lips; it provoked a greater clatter of leaves from the darkness.

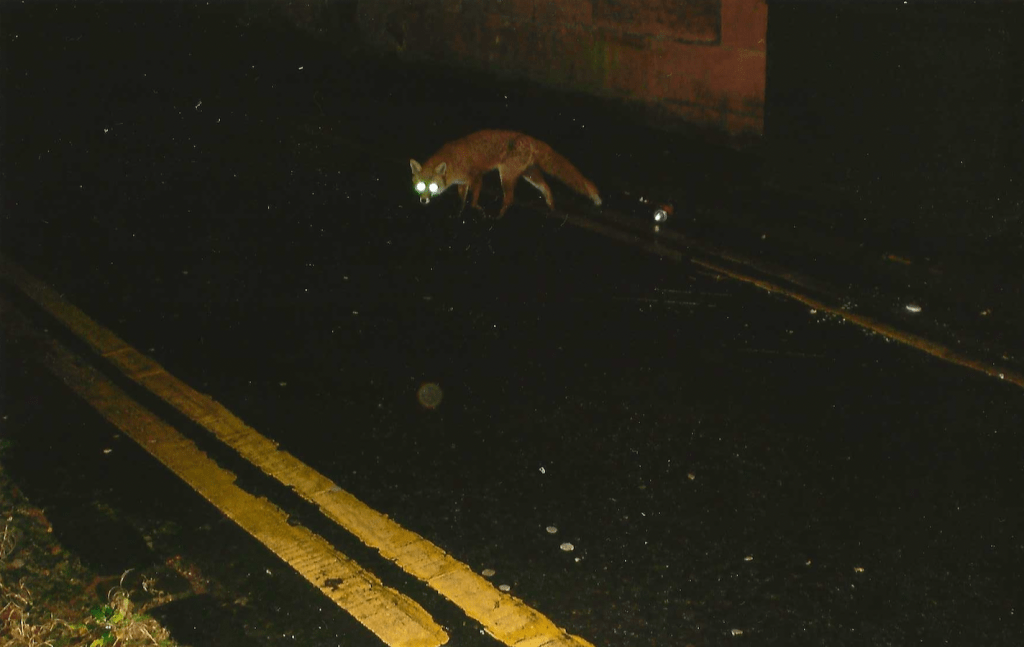

The nearest foxes ran spookily sideways and back into the shadows, then other ones ran forward and glowed their eyes like a flicker of lamplights. To my astonishment, I realised that this tiny park was full of foxes – one even ran along the top of a high wall, silhouetted against the glow of the city. Together they chirruped and cooed in a flexibility of wordsong – sounds I’ve never heard foxes make in the hills. In an eldritch, unfamiliar swirl, more and more of them revealed themselves and vanished again like the monkeys which swing around King Louie’s temple in the Jungle Book.

Collective nouns are often unsuccessful. Skeins of geese and herds of cattle work because these creatures usually move together. But when solitary animals are given collective nouns, it’s more like a cute attempt at wordplay and humour – because you’d never actually see a “labour of moles” or a “romp of otters” in the wild. These words are pretty, but they defy ecological convention – and they fail because you couldn’t use them in isolation. Many collective nouns are so scarce and unnatural that nobody would know what you meant if you claimed to have seen “a romp” or “a labour”. You’d have to explain yourself – and in doing so, you might as well have explained what you meant from the start. And here were seven or eight foxes in “a skulk” – it’s no wonder words failed me.

I’m used to the slow, collective movements of sheep and cattle. I can see beyond the decisions of flocks of chickens or aylesbury ducks and steer them accordingly – but wild animals are more likely to lie alone or in pairs. Chase a hare and the movement is only its own; even when it echoes what a different hare did yesterday. It’s in the nature of nature to think on its feet, and if the same factors dictate the same outcome, so be it. But what I mean here is the distinct way creatures have of moving together; deferring to a leader, even when that leader is hard for you and I to tell apart from the throng. When you learn how an animal moves, remember that a different set of rules will dictate how animals move as a plural.

Having never seen more than two foxes in one place at a time, this collective churn of creatures had an energy of its own – seven or eight individuals acted and reacted together to make something new. Working on the basis that it’s impossible for a fox to commit an un-fox-like act, it’s reasonable to divide the behaviour of these animals into two clumsy groups; “things I’ve seen or heard of foxes doing before” and “things I haven’t”. Both are authentic and true to the species, but it afterwards seemed like everything I’d ever learned about foxes amounted only to a small portion of themselves; simply a glimpse of what one individual may do on its own. It turns out that they’re something else in a group, and if these streetlit movements appeared erratic and patternless to a novice like me, perhaps they could also be resolvable if you chose to understand them – just as the churn of starlings or mackerel makes a fluid kind of sense if you watch it for long enough.

For more gregarious species, the opposite problem is equally true – when we see a starling on its own, we often assume that there must be something wrong with it. We stare at it in sympathetic curiosity, hoping that this perfectly individuated creature will soon be well enough to rejoin the massed propriety of a gang.

Leave a comment