You really need a reason to visit the Burrell Collection. Go without plans and the day will evaporate in a cobweb of diversions and distractions. There’s no theme or coherence to objects drawn together by the Edwardian philanthropist William Burrell, and even the loosest groupings have outriders and oddities which blast the narrative and set new angles against the flow. As you walk between the displays, it sometimes seems as though a pattern is about to emerge; details are sketched into place by a repetition of objects from Iran or China or ancient Egypt. But the pattern is only a stammer, and any sense of coherence will clatter away again in the tapestry room, or in the gaps left between odd-ones-out by Gauguin or Rembrandt.

It’s no complaint to mark the collection as a miscellany – Burrell bought what he liked and the venn diagram is bunched accordingly. There’s even fun to be had in the chaos of it all; a kind of sensory overload in the flicker of a hundred divergent threads. As a museum “for Glasgow”, it succeeds because surely there’s something for everybody there. It’s a generalist’s playground; a tapas of material culture from ancient Greece to Degas. But I have never come away from the Burrell Collection without a sense that it’s too much – and that instead of an unintelligible blur of astonishment, I would be more fulfilled by a day’s proper engagement with only three or four objects.

It’s fun to engage with the Collection as if it were a kaleidoscope. Patterns are inferred from the brilliant serendipity of randomness which jabs and pokes at your own memories and associations. It can be thrilling to go with the flow, but there are other ways to engage with the mess. Looking forward to a journey across Central Asia, I wanted to see if the Burrell could also work as a reference library to support my own slow (but rapidly expanding) construction of an imaginative landscape in the gap between China, Russia and India. There are many reasons why I’m heading east, but a key driver is that I simply can’t imagine what it’s like. I don’t know what I’m letting myself in for, and I know that preparation will only take me so far. So I’m reading frantically through a list of histories, travelogues and poetry from Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan; each book is a piece of the puzzle, and each step creates more headspace to play and enjoy the process of “looking forward”.

Beyond some beautiful embroidery from Uzbekistan, the most useful objects at the Burrell Collection come from opposite ends of the Silk Road. From “the near end”, there are some extraordinary Persian rugs and prayer mats on display, alongside a wealth of ceramic artefacts from Iran. From “the far end”, there’s a series of earthenware dogs and dragons which represent aspects of Chinese trade and culture. Acknowledging that there’s a tremendous amount of geographic space between these two ends, it is sometimes possible to look down the telescope of one towards the other – and if you can shield a sense of focus long enough to ignore a hundred distractions which lie between the two at the Burrell Collection (including a very alluring display of mudejar bowls), you can detect a connection between them.

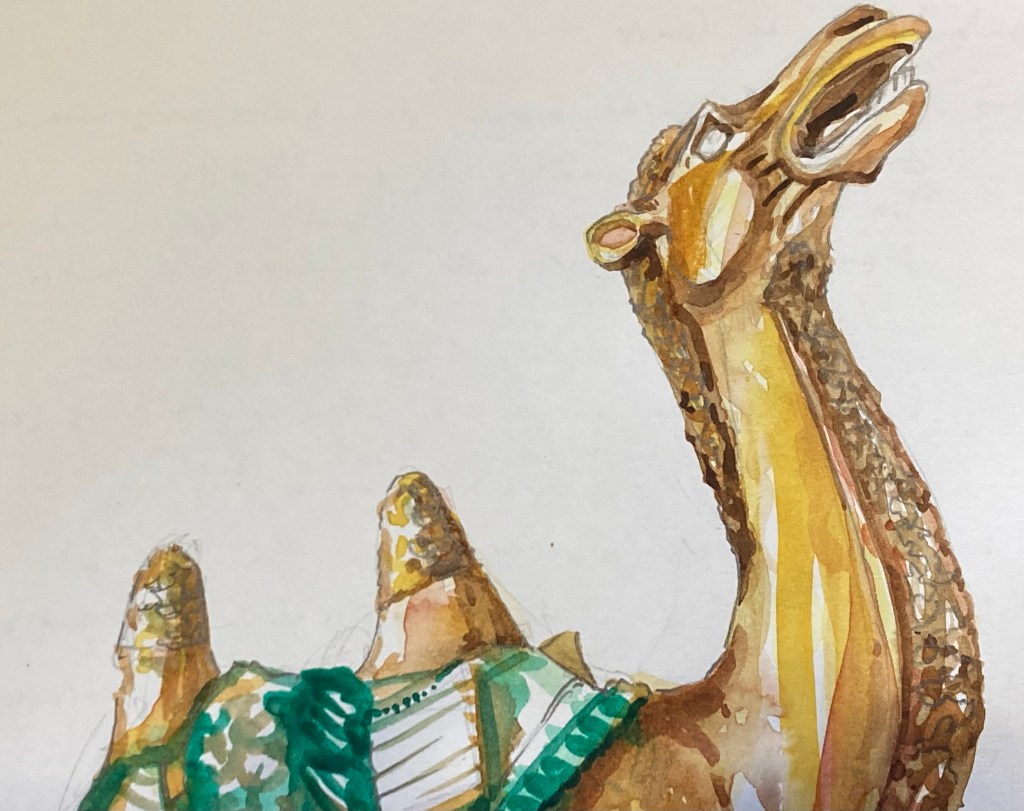

I’ve become obsessed by these Silk Road associations, and craning my neck to understand the links, I was overturned by a camel encounter. This came in the form of two earthenware figures from the Chinese T’ang Dynasty. One was laden with baggage; he turned his head back to grimace and gurn with an expression of revulsion and ugliness. The other had a rider in the form of a small Chinese woman.

Camels like these are of a type. They were produced to mark the funerals of wealthy Chinese traders in the 7th and 8th centuries who prospered as trading routes opened across Central Asia. If you search for them online, dozens of these earthenware shapes turn up in a range of glazes and styles in museums, auction houses and collections across the world. Importantly, they’re all presented in the same way; the hideous gape and the pendulous, textured coats which tumble down from the armpits, breast and briskets.

T’ang camels are a phenomenon, and William Burrell’s examples are just a small part of a much wider pattern. On the larger camel, the shining, semi-opaque glaze runs in trickles to a pattern of green and coffee-brown sags around the hips and upper thighs. At first glance, these dribbles look hurried and artless, but the runners actually reveal the bulge and contour of muscles and tendons; and where they pool in the textured representation of heavy hair, they heighten contrast like a cluster of barnacles on the hull of a ship. They’re clever because they elevate the ugly, functional symbolism of freight animals to a kind of glamour and celebration.

Typically, these camels are not displayed together. That would make too much sense for the Burrell Collection. Instead, they form part of separate exhibitions and stand several metres apart. Having seen and been struck by one, the second set my pulse racing. I’m a sucker for representations of nature, and my eye is forever drawn to tigers, hares and horses in the Collection – but the camels I saw were more than just ugly, partially-domesticated monstrosities – they gestured towards an entire landscape and culture based on trading routes, travel and the endless swirling mixture of cultures across Central Asia. This is what I was looking for, and while it’s not easy to follow a thread at the Burrell Collection, the ambition was rewarded. I didn’t go looking for T’ang camels, but my God did I find them.

Standing in a flood of summer sunlight, I painted one of the camels into my book. And when I came to look back at the page this morning, I’m suddenly struck by a realisation that in the hideous, squalling gape of that camel, there is a sound being made. As it bellows into the sunshine, that camel is doing something which has not been transposed into the glitter of glaze.

If you know the sound that camels make when they roar into the desert, these figures would certainly bring it to mind as a memory. But I have never heard it, and I have even begun to fill this gap with my imagination instead. Anticipation builds, and while the Central Asia that I am assembling in my mind’s eye is probably far from the truth, it matters to me. It’s a project which I knead and feed and thereby bring the pleasure of this journey closer. And it warrants some commemoration here – because unless I am very careful, everything I have imagined will be deleted and overlaid by reality.

Leave a comment