There are plenty of unsettling angles to ponder in Henry Williamson’s short story Zoë. The narrative follows Captain Horton-Wickham’s rescue of an otter kit which is orphaned when its mother is shot by a cruel and unfeeling fisherman. Reared by a cat from the local pub, the tiny otter is named Zoë – and it grows into a charming companion for Horton-Wickham, who lives alone after having been “crocked” by a rifle bullet during the First World War. But while Williamson’s animals often enjoy a moment of final redemption in death, there’s no relief to be found in the conclusion of this tale. Zoë is inevitably killed by the local hunt, and in a strange twist of fate, the field is joined by Horton-Wickham’s old enemy – the man who stole his wife before the War. Blinded by grief at the loss of his pet, the injured soldier sets out to kill the huntsman – but courage or capacity fails him, and he finally turns his gun upon himself. It afterwards transpires that the name of his departed wife was also Zoë.

Parts of this story are beautifully told, but it slumps to an abrupt conclusion in a jumble of bleakness, confusion and reality-stretching coincidence. It’s not Williamson at his best, but beside Tarka the Otter, Zoë offers some useful context for the writer’s own biographical connections to nature and hunting. Zoë predates Tarka, but the story lays down the same curious ambivalence to the ethics and morality of otter hunting. Horton-Wickham used to be an enthusiastic Master of Otter Hounds, but he has turned his back upon the sport. However, the connection endures in his imagination, and he has kept hold of the masks and the paws of old kills – they’re still on display in his house when visitors come to call. With typically Williamsonian ambiguity, the reader is allowed to decide how they feel about those who continue to follow hounds. During the final hunt, pretty girls and blithe children gambol in the stream, enjoying the sport for the sake of its spectacle – aristocrats and social climbers attend with a mixture of shame, curiosity and genuine fun. All of human life is here, and the sport is neither good nor bad; it’s simply a fact of life (and death).

Even the best and nicest people in Williamson’s stories exist in a countryside that is generally indifferent to concerns for animal welfare. Their natural world is hard and painful, and expressions of cruelty are complex and subjective – the fisherman who kills Zoe’s mother once shot his own horse and would have been prosecuted for it if he did not enjoy a position of small nobility. The cat which raises Zoë has been grievously mutilated by a gin trap – it shares its disfigurement with the wounded soldier; both are trapped in worlds of pain, but each shows warmth and tenderness to an abandoned wildling. Physical injuries and suffering are more than simple devices to evoke sympathy in the reader’s imagination; they’re the basis of an entire worldview through which the whole countryside is felt and heard. In his nature writing, Williamson’s human beings are often sketched in with the barest of details – but many are damaged or warped out of shape by trauma or loss. The countryside is indifferent to their suffering, but that suffering is the lens through which everything is seen.

Henry Williamson survived the First World War largely unscathed, but his experiences caused internal scarring which drove him to polar extremes of connection and detachment. He is certainly present in Horton-Wickham – when the isolated invalid passes his time listening to Wagner on the record player, it’s useful to know that Williamson often did the same. But beyond the author’s own preoccupation with pain, love and the redemptive potential of nature, Horton-Wickham rises through the rush into anger, vengeance and suicide.

Tarka the Otter is often described as a children’s book, and I was slow to discover it for that reason. But Tarka is too rich and complex to be limited by simple categorisations, and while it certainly works for children, there’s plenty more beneath the surface – not least in Williamson’s ability to balance accessible themes of riverside wonder against a hard, confusing expression of man’s relationship with nature. Zoë lies in a similar direction, but with a greater emphasis on human darkness and pain – and so I feel for the children who were delighted by Tarka and afterwards reached to consume anything else they could find by Henry Williamson. It’s a logical step, and one I often made myself as a child – to read one book in a genre and then want to read them all. But landing on Zoë, they would have found something far more adult and conflicted than anything in Tarka. Perhaps little boys would have cleaved to the tragic heroism of an injured man, but beyond some neat passages and a shimmer of the wild, the story is too conflicted and unbalanced to make much sense to a child.

I’m realising that the majority of Henry Williamson’s work was focussed upon human stories in the aftermath of the First World War. Nature writing provided him with fame and financial stability, but his heart was devoted to “grander” creative projects which he would have considered to have held greater literary merit. So it’s ironic that the only books which have survived to form his lasting legacy are Tarka and Salar – both of which are more like outliers in the Williamson canon. And so my fascination moves from an initial surprise that this lovely old Tarka-man somehow became a fascist – to focus instead on the fact that this damaged, irascible ideologue somehow wrote Tarka.

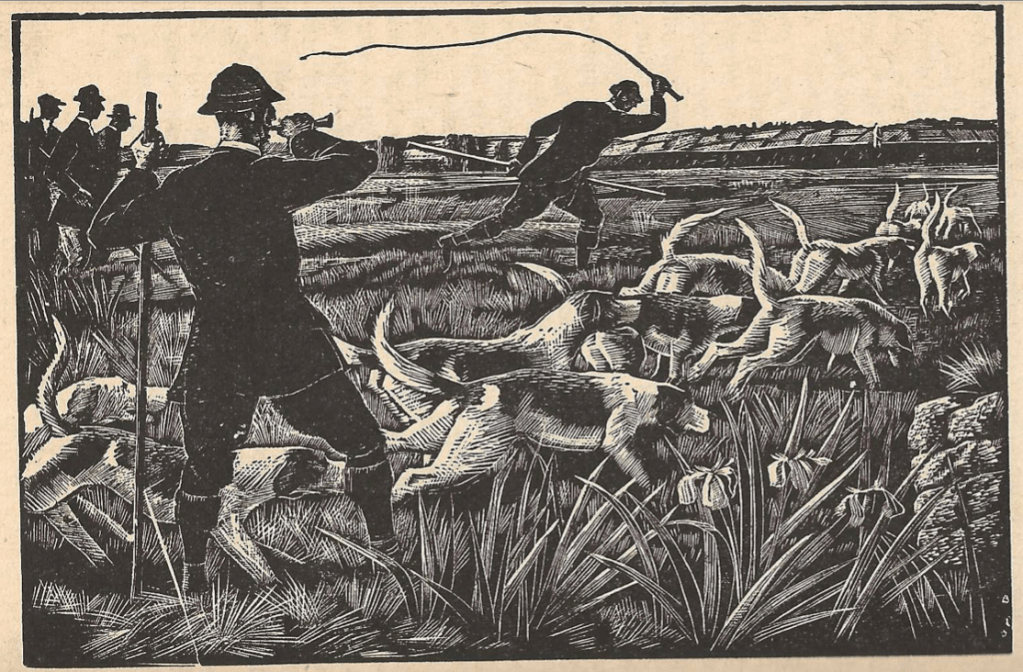

Picture: Illustration for Zoë by CF Tunnicliffe in The Old Stag, Penguin Books, 1942.

Leave a comment