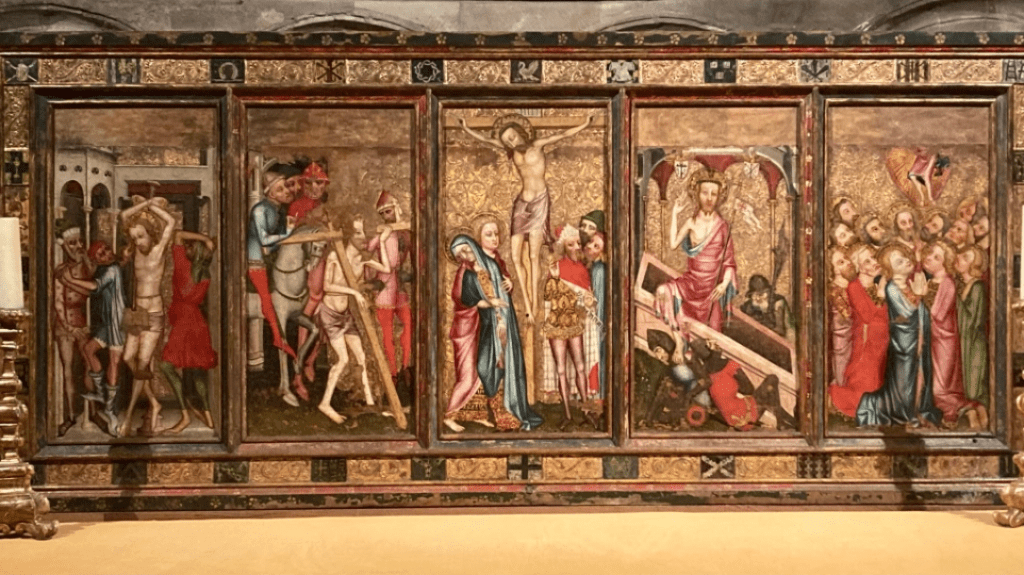

Norwich cathedral was cold as barn in December. I shivered in the aisles and gathered my coats around me. Every time the doors opened to admit new visitors, a bitter Scandinavian wind rushed in to gutter the candles and pull at the straw in the nativity scene. I found the things I went to see; I craned my neck for the famous cloister bosses and gaped at the Despenser Reredos, but all these things were strangely disparate, and minutes were spent walking between them. There wasn’t time to do them justice, and through no fault of its own, the building left me feeling empty.

I was ready for the service when it began in the darkness at four. I was given my choice of seats in the choir, but told not to sit beyond a certain point in the stalls. I misunderstood the instruction and sat beyond it, so when the grand procession entered and the choristers were sorted like playing cards to their benches, I found myself sitting beside one of the canons; a young, attractive man in his thirties. He smiled and didn’t seem to mind that I was in the wrong place; a spy in the beating heart of the service.

Anticipating Advent, the first reading came from Kings 1:18; the story of Elijah and the prophets of Baal. It’s where God is challenged to prove His existence by performing a miracle. I had always recoiled from the idea of such conditional faith – the very nature of God places Him beyond the status of a dancing monkey. So it’s hard to hear how Elijah frames that moment of truth. He is so certain of God’s compliance that he mocks and gloats at the prophets of Baal. He makes it easy for them and hard for himself, jeering and gurning with pantomime theatricals to such an extent that I start to wonder where his damn humility’s gone? In fact, with all that capering smugness, he’s almost worse than the blasted Pagans – but God rewards him anyway; He burns Elijah’s bull and proves His existence to ravening crowd.

The reading ended at verse 39, neatly excising the part about how the Prophets of Baal were afterwards executed for their faithlessness. The crowd is whipped to a frenzy of devout enthusiasm for God, but the message here is greater than this ugly show of “prove it” and “I told you so”. The message is revealed soon afterwards when we learn that Ahab and Jezebel returned to worshipping Baal. In time, the mob forgets the miracle and the bold demonstration of truth, and everybody returns back to square one.

The lesson here is really to explain the pointlessness of miracles. God cannot be expected to perform on demand to prove his existence like some desperate busker. That’s not how the dynamic works. But there’s a bigger and more pragmatic reason to sideline mind-blowing feats of magic and whimsy – because they don’t actually help to inspire belief.

Instead, the story of Elijah and the prophets of Baal teaches that magic and miracles fade; that when we demand “proof” of God’s existence, we’re barking up the wrong tree. Because real, substantive proof of God’s existence is everywhere, all the time – in the smallest glimpse of sunlight or mist in the morning; in love or the sound of wind in the trees. These are more compelling and convincing reminders of God’s presence, not least because they are everywhere and available to anyone who cares to detect them.

When I began this line of thinking towards Christianity, I was steeped in Twenty-First Century cynicism. Like an anthropologist, I wanted to unpick the riddles and see what a Christian sees – but I was also cautious of being pulled into something I couldn’t control. Christianity is nowadays presented as a trap or a snare for the credulous, so l embarked upon my missions like a deep sea diver, connected to fresh air and reason by an umbilical tube. I was guarding against a kind of manipulation that is imposed from the outside like a virus, but instead I have found religion based upon a simple reorganisation of things I already had.

Small moments are beautiful; life is powerfully brightened by subtleties. I am endlessly buoyed by my ability to access small and perfect moments in the day. In the peace and solitude of that calm, I have often found a special kind of meaning in the world around me. But I was keeping that fact in a separate box, away from this religious thought-experiment. After all, those moments are entirely mine and the connections I felt most dearly had nothing to do with theological dogma.

Approaching Christmas, it’s useful to focus upon details and a sense of presence in the moment. Kings 1:18 is not an obvious choice for Advent – but in the dead of midwinter, it’s helpful to remember God’s presence in smallnesses. Christians say that God proves his existence in the simple serenity of those moments; being alive to the robin and the rising moon. If I want to follow them, I have to concede that something I thought was “entirely mine” is not – it’s part of a pattern which runs through everybody and everything.

So as I walk deeper into this experiment, I find that in some ways, believing in God would simply require a shuffling of furniture – and I am already closer to this than I thought.

Picture: The Despenser Reredos at Norwich Cathedral, photographed 4/12/22

Leave a comment